Planning is important. Putting those plans into action is even more important. But when you do implement your plans, you need to make sure the job is done correctly.

This is especially the case in the area of trusts, where a badly implemented plan can sometimes be even worse than no plan at all.

In this month’s article, I illustrate this point by highlighting the story of Philip Macalister from New Zealand. It is an interesting and also slightly sad story made more powerful by the fact that I know Philip personally.

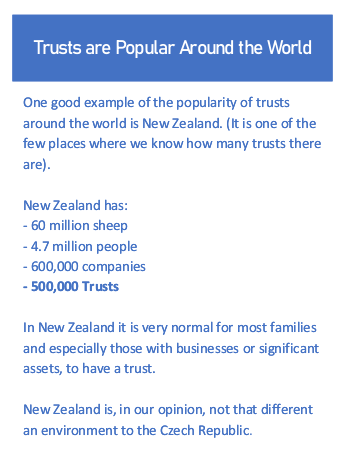

Philip lives in New Zealand As we have mentioned in the past, and as the box to the right illustrates, unlike the Czech Republic, New Zealand is a country of trusts.

Philip lives in New Zealand As we have mentioned in the past, and as the box to the right illustrates, unlike the Czech Republic, New Zealand is a country of trusts.

So in the area of trusts, New Zealand and the Czech Republic are very different. But there are other areas of life where our two counties are very similar. For example, many Czechs have cottages where they like to go at the weekends. To some people, this obsession with tiny houses can seem strange, but not to New Zealanders who also enjoy spending time in their weekend houses and holiday homes, which they call the “Bach[1]”.

Philip’s story can be read in full (in English) in this article from the newspaper in New Zealand. It is a great illustration of the importance not just of setting up a trust, but of structuring it correctly so that it works as it should.

The reason that the trust was set up in the first place is that Philip’s grandfather bought a cottage in 1920, and he wanted it to stay in the family after he died in 1967, for use by future generations. This is a very common and logical reason for setting up a trust. Putting the cottage in the trust means that it belongs to ‘the family’ but not to any particular person, it is not subject to future inheritance proceedings and if the trust is set up correctly, then it will also fairly manage the cottage into the future, avoiding the family conflict which is otherwise almost inevitable. It will also achieve the other goal, which is to make sure the cottage stays in the family.

So a trust was an excellent idea. Or at least it would have been a good idea if it had been established correctly

In fairness, the trust did its job for quite a long time, but in the end, it failed to achieve its purpose because although the cottage is still in the family, some family members, including Philip, have been ‘shut out’ against their will. At the same time, the trust caused rather than prevented family conflict.

These problems were all the result of the way the trust was designed in the first place. A better structure design could have prevented all this. As Philip himself says,

“You should always have an independent trustee. You need an odd number, so you could have one from either side of the family and an independent … And you need a mechanism to refresh trustees, . . . . every three years you could retire one on rotation. And with trustees the decisions should be unanimous.”

This is a good starting point and is one of the points we made in our article in 2015 on this very topic.

There are a few more mechanisms that we would also build into something like this to make sure that it works. If you are interested in a copy of a case study showing how a typical well-designed cottage trust looks please email us.

The moral of this story is to remind you of the need to make sure that you get professional help when setting up your trust. A do-it-yourself approach can save money in the short term but often ends up costing a lot more in the long term.

Caption: This is a picture of a typical New Zealand batch. If you would like to see a picture of Philip and the actual batch involved on this case you can find them in the linked article.

[1] This word is pronounced different from the name of the composer. In Czech, it would be written Bač.*