A Tale of Castles and Cottages

In this article, we continue our series on the positive uses of svěřenské fondy.

If you walk around Prague or any Czech city it’s easy to see derelict buildings – sometimes well located, formerly beautiful, buildings – slowly crumbling, seemingly uncared for and unowned.

Have you ever wondered about the reasons they have been abandoned? I am sure that each house has a different story, some of them very sad. But many of them will be in the state they are as a result of disintegration of ownership caused by poor inheritance planning.

Let’s take two, very different, families as examples of the problem – a problem which svěřenské fondy can solve

Family 1 – Von Bambus

The von Bambus family are a (fictitious) aristocratic family who can trace their noble roots back for hundreds of years.

The von Bambus family are a (fictitious) aristocratic family who can trace their noble roots back for hundreds of years.

Following the velvet revolution, their family castle and lands were returned to them. But now they have a new problem.

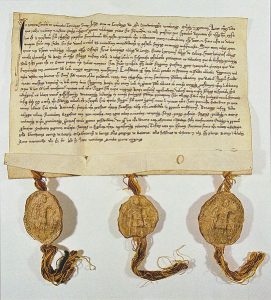

In the past, before communism, according to the doctrine of primogeniture, the family castle and lands always passed down from father to oldest son, who also inherited the aristocratic title. The other brothers and sisters never received any entitlement to the land although they were usually taken care of, at least to some extent, by their older brother.

Of course in the 21st Century we consider the doctrine of primogeniture as not just anachronistic, but also extremely sexist and generally unfair. However we also have to recognise that it did achieve one very important positive thing – it kept the family wealth and the castle intact in a single unit though the generations, which in turn preserved the strength and influence of the family.

And that’s the problem. If we apply normal inheritance rules to the von Bambus family, in the future in the first generation the castle has perhaps three owners, in the second generation, nine, in the third generation 27, and by that time the land will probably have all been sold and the castle will be a crumbling ruin, after all, who’s going to look after it? Who’s responsible for the costs of its upkeep? Who makes all the decisions? In theory, everybody does, but in practice 27 people will never agree on anything, so the end result is that nobody can do anything.

Another problem is that the assets won’t stay in the family. Due to bankruptcy, divorce etc. ‘outsiders’ will increasingly become owners of the estate.

The end result of the modern law will be the loss of the property to the family and the loss of the tradition and history of which the von Bambus family is so justifiability proud.

In order to solve this problem, families such as the von Bambus are looking at svěřenské fondy as a way to keep the concept and positive traditions of primogeniture alive, and as tools to keep the newly restored family estates intact, but without the negative aspects of the past.

The von Bambus family set up a trust, and appoint the oldest son (the one who would now be the Count, if the aristocracy still existed) as trustee. The trust deed provides that the role of trustee is passed down through the generations in exactly the way the noble title would have been in the past, except that, like the British royal family, they have removed the sexist element by allowing the oldest child (son or daughter) to inherit. However, unlike in the past the trust contains provisions that specify that the assets are held by the oldest child not as absolute owner, but as trustee for the benefit of all members of the family.

This structure allows the family to keep the family estates intact. It allows them to ensure that all members or the family benefit and are treated fairly. It also centralises the management of those estates into the hands of a single person the ‘Count’ (or ‘Countess’) so that important decisions can be made easily and quickly. This structure also means that the trustee has a clearly defined responsibility towards the other members of the family.

This is a fair and workable structure that gives the family ‘the best of both worlds’.

Family 2 – the Novaks

The Novaks, (also fictitious), are not aristocrats – they can’t trace their family history back much further than their grandparents. The Novaks are ordinary Czechs.

Even so, they can benefit from the same concept as the von Bambus. Mr and Mrs Novak live in Prague but own a valuable cottage in Jizerské hory. They have three adult children who grew up going to the cottage – which is full of strong family memories. Two of the children use the cottage regularly. The third child does not like the mountains, and never goes there. He would like his parents to sell the cottage.

Of the two children who use the cottage, one is a successful businessman who already contributes almost all the maintenance and repair costs. His family visits the cottage on average once a month. The other has a factory job, but he and his family love the mountains and he works hard to keep the grass cut etc. They visit most weekends.

Each of the three children has three children of their own, meaning that in the next generation, the cottage could potentially have nine owners

Mrs and Mrs Novak can see the obvious potential for family conflict on the horizon. They also want to ensure the cottage stays in the family, and to avoid future potential family conflict

Mr and Mrs Novak can set up a Trust in almost exactly the same way as the von Bambus family. Instead of the eldest son, they would typically appoint an uncle or other independent and trusted persons to manage the cottage for the benefit of all the family over the generations ahead. Such a structure can allow the family to ‘buy out’ those who wish to sell, and can make important decisions about maintenance and how the costs are to be paid. What’s also important is that, even if children get divorced, or become bankrupt, a trust will keep the cottage within the family, and available for the benefit of all family members

The structuring of such a trust can be quite complex, and professional help is required. But once the trust is in place, it typically runs very smoothly and for as long as it is needed.

In other words, if you fail to implement a business succession plan, then your business will probably fail. So the consequences of a bad business succession strategy are far worse than a bad marketing strategy; put simply, your factories will close and your assets will be sold at ‘fire sale’ prices, your employees will lose their jobs and the enterprise you have spent so many years building and developing will be gone – along with a good part of your accumulated family wealth.

In other words, if you fail to implement a business succession plan, then your business will probably fail. So the consequences of a bad business succession strategy are far worse than a bad marketing strategy; put simply, your factories will close and your assets will be sold at ‘fire sale’ prices, your employees will lose their jobs and the enterprise you have spent so many years building and developing will be gone – along with a good part of your accumulated family wealth.

The von Bambus family are a (fictitious) aristocratic family who can trace their noble roots back for hundreds of years.

The von Bambus family are a (fictitious) aristocratic family who can trace their noble roots back for hundreds of years.

What’s not so good news is that due to inexperience, many (perhaps even most?) of the Czech Trusts established so far are fatally flawed.

What’s not so good news is that due to inexperience, many (perhaps even most?) of the Czech Trusts established so far are fatally flawed.